We’re living through a new wave of identity fever in the development sector, with systems like Aadhaar proposed as the panacea for all kinds of problems, including national security and economic development, identity fraud and improving access to government services.

But the most important issue here isn’t one that only affects Aadhaar—this is about the negotiation between designers and users that affects every identity system, anywhere in the world, from India to Nigeria, Afghanistan to the United States.

As Caribou Digital’s Emrys Schoemaker argues:

“It’s not about designing a technology better, or figuring out what’s going to make a problem easier to manage from the perspective of the designer. It’s that, if you start thinking how users experience their everyday lives, you may not end up focusing on the same problems at all. Focusing on users can ensure that you’re focusing on the most important issues, as well as the most important technologies that might be developed in response to them.”

In her book When Old Technologies Were New, Carolyn Marvin uses the phrase “cognitive imperialism” to describe how technology pioneers project their own views of the world onto their technologies without considering the real needs of their end users. Meanwhile, Wiebe Bijker’s history of the invention of Bakelite lays out the theory of the social construction of technology—a history of how the people inventing things aren’t necessarily the same people who know their true potential.

Within the technology industry, these kinds of analyses that put the needs of users ahead of what the designers assume they need are quite common, and in some cases can be very successful. But this isn’t the case in the identity technology sector. The risk for ID tech is its greater chance of ineffectiveness, as it tends toward the top-down, the centrally planned, and the bureaucratic. The momentum in today’s dialogue around identity for development either risks missing out on the user’s needs altogether or until it’s too late, as analysts like Richard Heeks have argued.

Ultimately, the success of identity systems is not binary. It’s not just about counting the numbers of adoptees and refuseniks. Our research is showing that user adoption is far more complex, nuanced, and contextual. It hinges on how the mosaics of users’ lives and needs map onto the promises of identity technologies, not on whether politicians can successfully pass legislation to impose them. It’s not about whether people adopt an ID; it’s about whether they can and do use it effectively.

Technology development is a constant tussle between the intentions and assumptions of designers and inventors, and the social contexts of the people who actually use their creations.

There are plenty of examples of this in all kinds of fields, from pedestrians carving “desire paths” through park grass to the 1980s battle between VHS and Betamax (which wasn’t settled by the porn industry backing VHS, as is commonly believed, but rather by Sony not realizing that consumers valued being able to record for longer than an hour more than picture quality). This applies just as much to the identity technology sector.

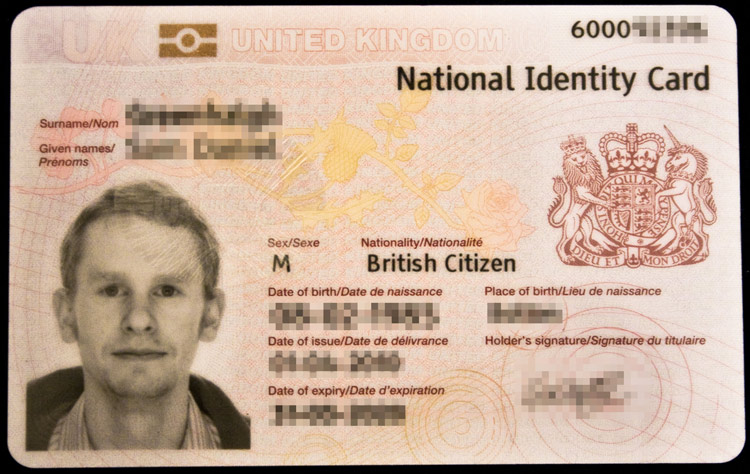

We can see that in the United Kingdom, which intended to introduce a new ID card post-9/11 as a way to improve national security; it was, however, rejected by citizens, the academic and political elite for being part of a growing “surveillance state.”

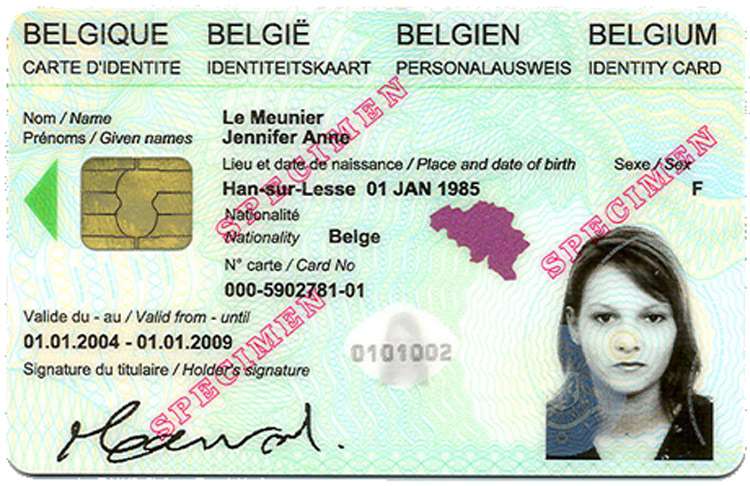

Meanwhile, everywhere else in Europe a national ID program is completely uncontroversial and trusted—go to, say, Belgium, where a similar card was launched in 2003 and had reached 100 percent adoption by 2011, and you’ll find Belgians using it for everything from reporting crime to digitally signing documents.

In Nigeria, though, the post-2007 rollout of a national identity system has been mired in controversy. The one-size-fits-all card, provided by MasterCard as a debit card and legally mandated ID for accessing services like voting, has managed to offend almost every demographic. It’s seen as a wasteful white elephant. In Afghanistan, the e-Tazkira card is largely viewed as a good idea in theory, but there’s continual controversy over what kinds of personal information (ethnic, tribal, and more) should be included on each person’s card. (This extensive report from the Afghanistan Analysts Network by Jelena Bjelica and Martine van Bijlert is well worth your time if you’d like to know more.)

A new ID gains favor, or not, for a number of different reasons. But the idea of success or failure is itself also open to interpretation. For example, take a look at the curious, extraordinary example of Estonia’s e-residency, launched in December 2014 and available to non-Estonians for €50, a photograph, and a copy of your fingerprints. It gives anyone the ability to found a company in Estonia and take advantage of the country’s world-leading digital bureaucracy, where it reportedly only takes five minutes to file a digital tax return.

There is no cultural pressure or incentive to become an Estonian e-resident. It’s a purely economic form of citizenship, and, as Dan Hill writes in Dezeen, it’s “a provocation about 21st-century citizenship.” The people who sign up for it are a globalist, entrepreneurial class who are already more likely to be citizens of more than one country. For them, an investment in one more may well seem prudent.

So far, almost 17,000 people have signed up for e-residency in Estonia, and the 1.3 million-population country wants 10 million e-residents by 2025. But will it be a success if it hits that target? Or will it be a success if it, instead, sparks a trade war in digital bureaucracy and national identity between neighboring European countries?

As we continue with each episode of this identities project, we’ll be building a map of the social mosaics that bind people together—and how their senses of identity develop out of them. Each story we share will be a corrective to thinking too much in terms of technology or policy, and remind us to look instead from the perspective of the user. Identity systems might develop from the complex interactions of the market and the state, but like all technologies, they don’t succeed unless the people they seek to represent embrace them.

Read Article Two: Adopting New ID Systems Often Means New Mistakes for Users to Fix